History & Language

Descending from voyagers and sailors, the history of the South Seas is as colorful as the pareos that adorn both locals and guests. Brave, courageous, and daring, the first settlers of French Polynesia navigated stormy seas and uncertain waters to find new land. From the invasion of European explorers to the French Immersion, the bright spirit of the Polynesian people never dulled, and instead transformed into the warm, vivacious culture that welcomes you to their islands today.

Introduction To The Great Migration

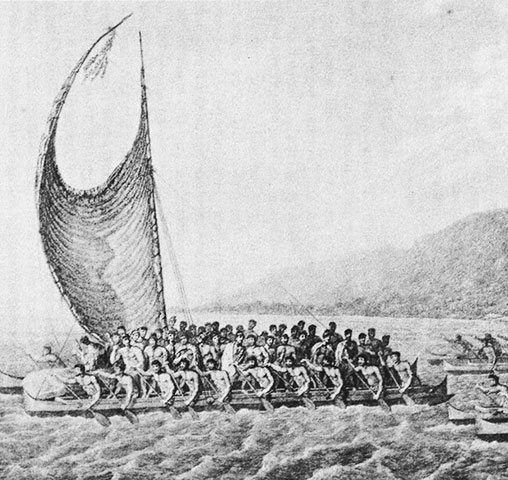

Around 4000 BCE, the seafaring people of the Solomon Islands left the comfort of their sandy shores to travel into the vast unknown. Guided by the winds and sea, they sailed across the Pacific to settle Tonga and Samoa, before pressing on to find Fiji and Vanuatu.

After 300 years spent hopping from island to island, they fell into what’s known as “The Long Pause,” which researchers believe to be caused by a lack of technology to navigate the strong winds surrounding both Tonga and Samoa.

Island Hopping – How Polynesia Was Settled

Over the next 2,000 years these early settlers revised their ships to suit the gales and ventured out once more. With newly advanced technology, they branched out farther than they had previously, reaching the picturesque islands of Hawaii and the cerulean waters of Tahiti.

According to local legends, an explorer named Kupe was the first to reach the lush land of New Zealand in his waka hourua, or voyaging canoe. Small groups of Polynesian people followed after and became known as the Māori – “the original people.”

Let Me Tell You A Story

When you visit the islands, you’ll be immersed in a culture rich with storytelling. Long before it was common to record history with ink and paper, the Polynesian people passed down the knowledge of their ancestors through speeches, myths, and waiata, or songs. The men and women of the South Seas believe that creativity is a gift bestowed by the divine, through a powerful, supernatural energy called mana. While everyone has the potential to increase their mana, some are born with more than others, and those people are often chiefs or priests of the village.

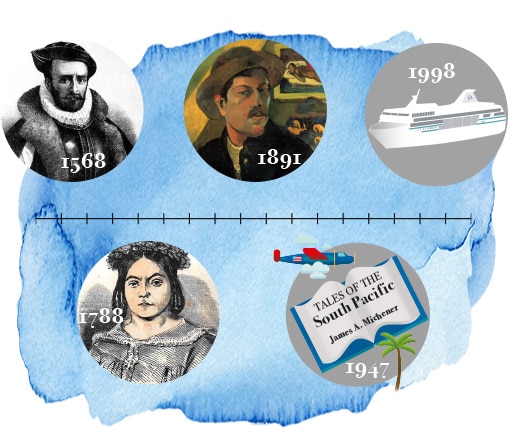

Timeline

Around 826 B.C.E: The Solomon Islanders reached Tonga.

1568: Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira reached the Solomon Islands.

1595: Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira reached the Marquesas Islands.

1767: Tahiti is claimed by the British.

1768: Louis-Antoine de Bougainville visits and claims Tahiti for France.

1769: Captain James Cook visits Tahiti for the first time.

1773: Captain James Cook leads mission to explore the rest of the South Pacific.

1779: Captain James Cook is killed in Hawaii.

1788: The Pōmare Dynasty is established.

1842: A French protectorate is established over Tahiti.

1865: Chinese laborers arrive in Tahiti, marking the beginning of the Chinese community.

1880: Tahiti becomes a French colony.

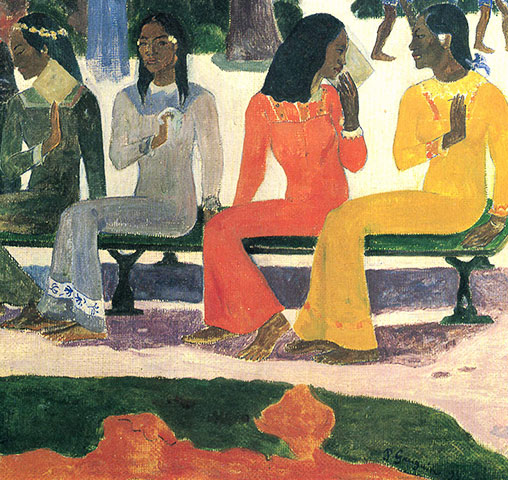

1891: Paul Gauguin goes on a self-imposed exile to Tahiti.

1947: Tales of the South Pacific is published.

1957: The name “French Polynesia” is chosen.

1973: A new law granted French citizenship to all people of Chinese descent in French Polynesia.

1980: The Tahitian language becomes the 2nd official language, after French, in French Polynesia.

Explorers — Logs, Lore And More

Once you step onto the dusty-white shores of Tahiti, it’s hard to leave. That’s why the history of these idyllic islands is filled with explorers, artists, and people from all over the world.

Álvaro de

Mendaña de Neira

Spain

Captain James Cook

Britain

Paul Gauguin

France

James Michener

United States of America

Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira—A Spanish explorer who set out to find riches in the “great south lands” of the South Seas in 1567. He is credited with “discovering” the Solomon Islands in 1568 and the Marquesas Islands in 1595.

Captain James Cook—A surveyor in the British Royal Navy, he was commissioned to sail scientists to Tahiti in 1769 to chart the course of Venus. After exploring Australia and New Zealand, he led a mission to further explore the South Pacific in 1773, before being killed in Hawaii in 1778.

Paul Gauguin—A French painter, and our namesake, who found self-imposed creative exile in Tahiti in 1891. Using saturated colors and bold contrasts, he loved to depict modern European constructs, like Mother Mary, as Tahitian people.

James Michener—A veteran turned novelist; he used his wartime experiences in the Solomon Islands during World War II to write his Pulitzer Prize-winning book Tales of the South Pacific in 1947. Enamored by the story, Rodgers and Hammerstein adapted the tale into the much-loved musical–South Pacific.

The Pōmare Dynasty

The Pōmare Dynasty ruled the Tahitian islands from 1788 until 1880 and consisted of five rulers—Pōmare I-V.

Pōmare I, also known as Tu or Outu, was the first king of Tahiti and the founder of the Pōmare Dynasty. He ruled between 1788-1791 and united the many chiefdoms of Tahiti into one kingdom.

Pōmare II began his rule in 1803 before being recognized as the supreme sovereign by the ruler of Hauhine and was forced to take refuge in Moorea in 1808. In 1815, he returned and defeated his enemies at the Battle of Te Feipī. After his victory, he was recognized as the true king of Tahiti. He embraced Christianity during his reign and established a “missionary kingdom,” ruling by a scriptural code of law.

Pōmare III began his rule in 1820 after the death of his father, Pōmare II. As he was only 1 year old, he ruled under the regency of his mother, stepmother, and aunt.

At age 13, Queen Pōmare IV began her rule in 1827 after the death of her younger brother Pōmare III. She was the longest reigning royal, ruling Tahiti until 1877. In 1842, she deported two French Roman Catholic priests, leading the French to establish a protectorate over Tahiti.

Pōmare V, Queen Pōmare IV’s son, was the last king of Tahiti, ruling from 1877 until Tahiti was proclaimed a French colony in 1880.

French Immersion

The indigenous societies of the South Seas were drastically affected by the influx of Christianity and French culture. Maraes, or temples, were destroyed, tattoos were banned, and traditional dances and ceremonies were claimed to be “too erotic and inappropriate.” In fact, when Paul Gauguin exiled himself to Tahiti in 1891, he was appalled to see how much French colonization corrupted the island. Thankfully traditionalism has found its way back to the shores of Polynesia, perfectly blending the vibrancy of Tahitian culture with the relaxed energy of the French shoreline.

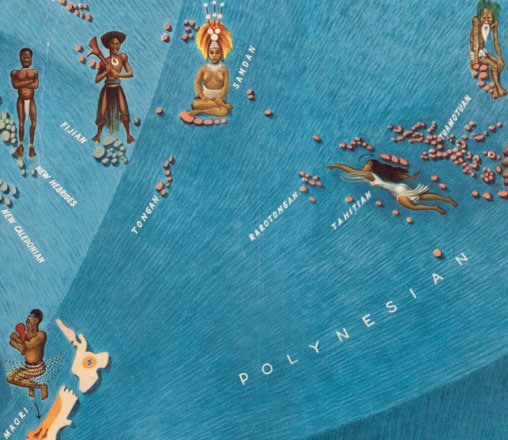

Language – Who Speaks What, Where

Where you are and who you’re talking to becomes important when you’re here in the South Seas, as you may run into a couple of different languages and dialects. While French is considered the national language of French Polynesia, Tahitian is just as common—with some islands having additional dialects. If you don’t happen to speak French or Tahitian—no worries! The staff on the ship, in hotels and at guest houses in the islands speak English.

Languages and dialects by Island:

Cook Islands: English, Rarotongan (Maori)

Society Islands: French, Tahitian

Hawaii: English, Hawaiian (limited)

Tonga: English, Tongan

Marquesas Islands: French, Tahitian, and Marquesan

Fiji: Fijian, English, and Fiji-Hindi

Tuamotu Islands: French, Tahitian, and Paumotu (Tuamotuan)

Common Tahitian Phrases

Hello: la Orana (yo-rah-nah)

See you later: Nana (nah-nah)

Welcome: Maeva (mah-yeh-vah)

Thank you: Maururu (mah-roo-roo)

Cheers: Manuia (mah-nwee-ah)

Beer: Pia (pee-ah)

Yes: E (ay)

No: Aita (eye-tah)

I love you: Uua here vau ia oe (oo-ah hay-ray ee-ah oh-ay)

Spirit: Mana (ma-nah)

Ocean: Moana (moh-wah-nah)

Island: Motu (mo-too)

Fare

(fah-reh)

house or home

Fenua

(feh-noo-wah)

island or earth

Marae

(mah-rah-eh)

meeting grounds or temple

Tane

(tan-neh)

man

Vahine

(vah-he-nay)

woman